Vietnamese War Dead

Today is Veterans Day in the United States, Remembrance (or “Poppy”) Day in Commonwealth nations, and le Jour du Souvenir in France. In Vietnam, it’s not celebrated at all, but that wasn’t always the case.

Unlike the United States’ vaguely-defined Veterans’ Day, in the places where the holiday is elsewhere celebrated it remains rooted in the specificity of the Great War, even as those memories to be recalled have virtually receded beyond the limits of the human lifespan. In France and elsewhere in Europe it’s the dead in particular that are the focus of the day’s attention, and one need not visit in November to witness its significance in historical memory.

Once they move beyond the famous Normandy sites, visitors to France are inevitably struck by the profusion of memorials celebrating not World War II but the war that preceded it. These monuments aux morts are sometimes modest, often grandiose, and usually moving through those lugubrious atmospherics particular to such architecture. Every village has one — the great film Life and Nothing But pokes fun at the desperate effort of villages without war dead to contrive a few corpses — and cities can have multiple monuments, often by neighborhood, all erected in the years that immediately followed the 1918 armistice.

Of course, “France” in the 1920s was a much bigger place than it is now, and the commemoration of war dead extended to colonies like Indochina, where under emperor Khải Định the Vietnamese in 1920 erected an enormous memorial in the imperial capital Huế. The site was — and is — nothing short of stunning. Situated on the right bank of the Perfume River, one side of the monument looks across the water at the ancient citadel, and the other side faces the elite National High School on Lê Lợi boulevard.

Quite unlike the monuments in metropolitan France, this one is resolutely “Vietnamese” in design. Though I knew little about it, I was eager to see this site when I visited Huế last month. In spite its remarkable state of disrepair, it’s still stunning, aided in no small part by its location, but also, at least to this author’s eyes, its surprisingly antique appearance. Although only in its ninetieth year, the monument looks far older thanks to air pollution, tropical climate, and a unique sort of neglect.

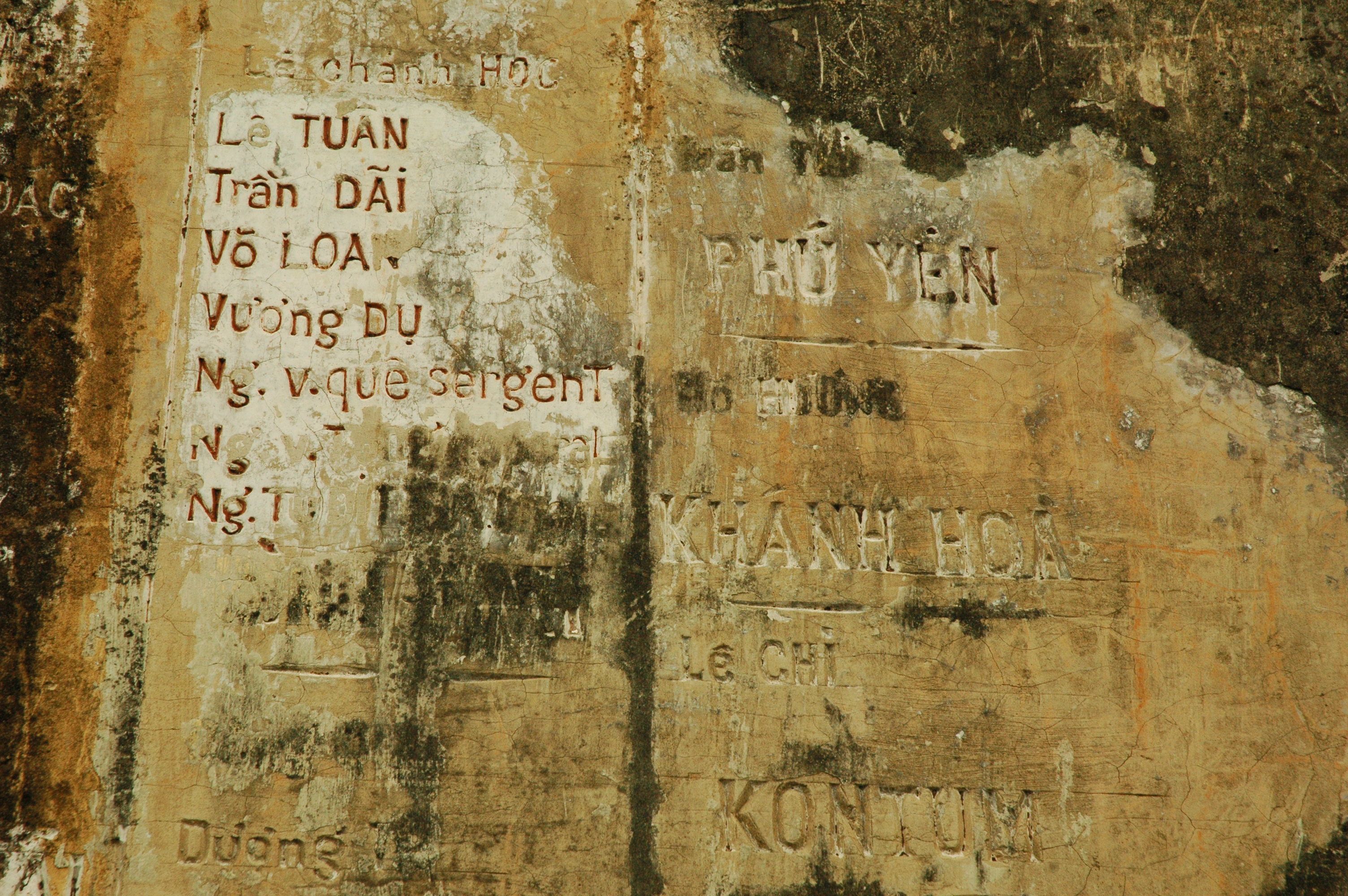

The front of the monument has two large blank rectangles which have been smoothed over and painted yellow. What happened here? Wikipedia dryly notes, “Previously, the front side of the monument had the names of 31 French and 78 Vietnamese in the center which later were effaced.”1 We might have guessed as much, that something had been removed. Around back, surprisingly, one can actually witness this destruction in progress.

Now, before I proceed, I can already hear the objections that Vietnam is a poor country with better ways to spend money than fixing up old “French” war memorials. Other nearby sites, like the royal tombs, have no small amount of graffiti (though they always at least post warning signs). I’ll just say that Huế is anything if not a tourism town, and right across the river there is a remarkable effort underway to rebuild essentially anew the imperial palace, utterly destroyed in 1947 and 1968. What interests me here is less the politics and economics of preservation and more the how and why this monument is actually being used.

If the monument were simply undesirable, why not simply demolish it? The Wikipedia article goes on to explain that “the monument has been retained because it expresses the traditional beauty of Hue’s architecture and is harmonious with the National School’s landscape.” And indeed, though names are quite literally being scratched out of the historical record, the monument hasn’t been entirely neglected. The side that faces the street has fresh paint, and the square surrounding it is tidy and unobstructed.

What I suspect is going on here is that these particular dead soldiers don’t fit easily into any acceptable narrative of Vietnamese history. One can easily deride Khải Định as a puppet or a collaborator of the French, and any reference to him invariably does. But ordinary Vietnamese soldiers who died fighting in World War I — and here, importantly, not “against” Vietnam in the way that VNA and ARVN forces can be painted — are a much trickier case. I don’t yet know the circumstances of the removal of the names on the front of the monument, but what I see happening today doesn’t seem particularly sinister. What’s unavoidable is the conclusion that no one here really wants to remember these people at all.

-

Wikipedia contributors, “Đài tưởng niệm chiến sĩ trận vong (Huế),” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, http://vi.wikipedia.org/wiki/Đài_tưởng_niệm_chiến_sĩ_Trận_vong_(Huế) (accessed 11 November 2010). Translation mine. ↩

Leave a comment